Conserving Arowanas Needs More Than Releasing Fish

(Part 1)

This fish is now rarely seen in rivers and lakes. Fortunately, it could still make a comeback. But first, how did this once common food fish shoot to popularity and became one of the world’s most expensive pet fish?

Writers: YH Law and Tracy Keeling

Editor: SL Wong

Published: 12 March 2024

Part 1 | Part 2

(Feature video: Asian arowanas, such as this golden variety, mesmerise fish hobbyists worldwide. Though they are abundant in farms and aquariums, they have been endangered in the wild for 50 years. | Video by YH Law)

Chapter 1: Arowanas everywhere but home

ONE MORNING in early January, Mohamad Zuhril Hakim bin Zaili packed his angling rods and drove 20 minutes towards Lake Bukit Merah in Perak. From above, the man-made lake looks like a lady in a dress, her long unbridled hair blowing in the wind. A train track runs across the lake from east to west.

Hakim has been fishing at the lake for 5 years. The 34-year-old with a black scraggly beard is particularly fond of a spot he found 2 years ago at the western bank, just north of the train track. Clusters of a woody pandan with thorny stems called rasau (Pandanus helicopus) grow along the bank, and their submerged roots attract many fish. Hakim has caught common species like lampam there, but also the lake’s much rarer and most famous resident: the Asian arowana.

The Asian arowana (Scleropages formosus) is a sleek and shiny freshwater fish that has fascinated fish hobbyists for decades. Adults could grow longer than a metre, but even a 15cm juvenile could sell for more than RM1,000. Pet owners want more arowanas, and breeders strive to meet their demand.

Arowana farms line a canal that flows west out of Lake Bukit Merah. In each farm are tens to hundreds of rectangle dug-out ponds where workers raise thousands of arowanas. The fish come in various colours: golden, metallic blue, red, albino. Workers grade, pack, and ship the fish live to aquariums across Malaysia and overseas. Hakim worked at one of the farms too.

In the wild, however, the Asian arowana is endangered and rarely seen. Lake Bukit Merah, 3,600 ha in size, was once a haven of the much sought-after golden Asian arowana. Yet nobody has caught a wild arowana there for nearly 20 years. Zealous collectors for the aquarium trade from the 1960s to 1980s have largely emptied the lake and surrounding rivers of wild arowanas. Wild populations elsewhere suffered the same fate too.

But efforts are underway to make a happy conservation story out of the Asian arowana.

In 2018 and 2022, Bukit Merah arowana breeders and the government released about 300 adult arowanas into the lake as a conservation measure. Since then, arowanas have been spotted around the release sites. Hakim himself has caught 8 adults.

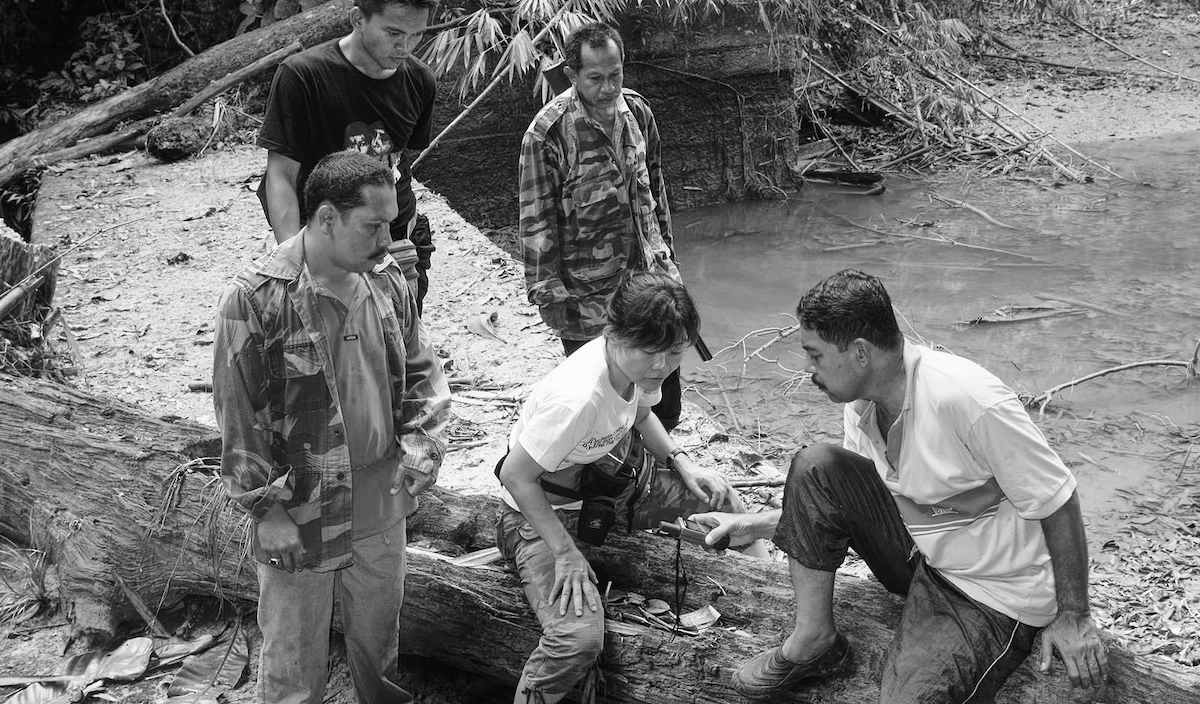

The government plans to release more captive-bred arowanas. On 9 January, fisheries officers held a two-hour dialogue with Bukit Merah fishermen and arowana farmers. The officers asked the locals to support future releases. If the fish is no longer threatened in the wild, it would help to open access to the market in the United States that prohibits the import of endangered species. Participants asked about the results of the earlier releases in 2018 and 2022 and the lack of protection for arowana in the lake. Nobody gave a straight answer.

However, arowana conservation would need more than releases of farm-bred fish. To thrive, wild arowanas need safe and food-rich environments to feed and breed. But from where Hakim cast his line and bait, Lake Bukit Merah does not appear to be such a place.

The first time he stumbled upon this fishing spot, he had to slog through a forest. Now he drives there on an unpaved road built for a new durian plantation. The forest was cleared and the bank left barren except for scattered clumps of rasau and trees. Hakim sits between two rasau clumps and casts his line into the brownish-green lake.

He is catching far less fish than before. “The water is so turbid,” he says. He blames the soil run-off from forest loss. He points to the newly cleared hill behind him, its yellow clay soil exposed on steep slopes. “The soil would surely wash into the water. It’s someone’s land; what can we do?”

When the water is clearer, one might be lucky enough to see arowanas swimming among the rasau, he says. Local fishermen and anglers say they release any arowana they catch. But the locals claim that “anglers from outside” had accidentally killed arowanas when they tried to keep or sell them.

Hakim and many locals see Asian arowanas, especially the golden variety, as an icon and heritage of Bukit Merah. They would like the lake to once again be a haven for Asian arowanas.

What can we do to re-establish a thriving wild arowana population in Bukit Merah? To get the answer, Macaranga spoke with nearly 30 arowana farmers and traders, fishermen, scientists, and government officers. Arowana conservation is not simple, but it is feasible. What is needed most is a fraction of the doggedness that drove us to kidnap Asian arowanas from their homes into our own to satisfy our viewing desire.

Chapter 2: Wild times

About a century before Hakim came to Bukit Merah, British anthropologist Ivor Hugh Norman Evans visited the lake in 1922. The Bukit Merah reservoir, as it was called, was built 16 years before by British engineers to irrigate the vast expanse of paddy fields to the west. By the lake, Evans snapped a photograph of fish strung on three lines, all caught with angling rods. Among the 68 fish were 6 Asian arowanas.

Appearing in the 1923 Illustrated Guide to the Federated Malay States, Evans’ photo is the first published evidence of Asian arowana in the peninsula. It also captured a scene that was never to be witnessed again: a time when arowanas were so common in Bukit Merah that they made up nearly 10% of fish catch. That was a time when elephants still roamed the coasts of Perak, and travel guides ran 30 pages of instructions on hunting the seladang, rhinoceros, and tigers in Malaya.

Asian arowanas are known for their speed and strength, as these red tail golden arowanas demonstrate as they swim against the current in an aquarium. (YH Law)

The Asian arowana is a freshwater fish. It lives in lakes, rivers, and swamps from Cambodia to Peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra, Sarawak, and Kalimantan. A top predator, the fish embodies speed and strength. It scans the depths and above with enormous eyes and a pair of bristles (called barbels) on the tip of its tapered mouth. Armed with hard scales with highlighted rims and a powerful trio of fins at the end of a long straight back, adult arowanas have little to fear. When provoked, it leaps out of the water.

Asian arowanas vary in colour and genetic makeup across their range, though all belong to the same species. (Note: Scientists identified a new species in 2012 called Scleropages inscriptus found only in southern Myanmar. Asian arowana in this story refers to Scleropages formosus only.) The most prized varieties are the red arowanas in Kalimantan and the golden arowanas in Bukit Merah and nearby waterways. In Kedah and the East Coast of the peninsula, arowanas are of a green hue.

Unlike most fishes, the Asian arowana is a slow breeder. It starts to mate around 3 years old, and females lay 20—50 eggs at a time, each with an orange yolk as large as a marble. As the eggs sink to the bottom, the father scoops them into his mouth and nurses them there. During this time, he fasts and after 60 days, releases his 5cm long fry into the world.

Despite its slow reproduction, the Asian arowana flourishes in healthy environments. In the 1940s, villagers around Lake Bukit Merah were hauling up dozens of arowanas from the river for food at one go, recalled villager Syed Alwi, who was describing his childhood in a July 2002 letter to The Star. Likewise, a Bukit Merah fisherman told Macaranga that, in the 1950s, his father and uncle trapped 8 kg of arowana in a morning and sold them for 15 sen per kati (600 grams).

While Malayan villagers ate Asian arowanas, British officers loved fishing them. One such officer was Anthony Locke, who shared his adventures in the Journal of Malayan Angling Association. In 1954, he had fished for kelah, sebarau, and tengas in Sungai Terengganu (‘Sungai Trengan’) – all well-known feisty fish. But when an arowana bit his hook, it turned out to be the “finest fighter to be found in our rivers”.

The fish leaped 6 feet (1.82 m) out of the water, then dashed 45 m across the river, rocketed up a steep bank, arched its body, and spat out Locke’s line. Locke was awed. He called the arowanas “well educated” for their uncanny ability to dislodge a fishing line. To tackle an arowana, he wrote, “is certainly good for the fisherman who becomes a little too sure of himself.”

But good times in freshwater habitats were fading. In 1957, as Malaya won its independence, the parting president of the Malayan Angling Association warned his members of “insidious” damage to the rivers and fish within. In his farewell letter, HJ Kitchener flagged the dangers of pollution, overfishing, and the eventual loss of native fish. He implored “members and citizens to do all that is possible for the maintenance of clear clean rivers and other areas of freshwater.”

Kitchener was sadly prophetic. A decade later, the era of wild Asian arowanas would give way to the era of pet Asian arowanas.

Chapter 3: Into tanks

People recall differently how arowana shot to popularity in the pet trade. According to Ng Hang Yong, one of Malaysia’s earliest arowana breeders, a Malayan Chinese fish collector called Lim Yi Soon (transliteration) began delivering Asian arowanas to Hong Kong via Singapore in the 1940s. This collector harvested juvenile fish from forest streams and carried them in pails on foot and bicycle to buyers. He would stop often at streams to pour fresh, cool water into the pails to keep the fish alive.

But veteran pet store businessman Chew Seng Lye (also known as Chew Thean Yeang) claims he was the first to introduce Asian arowana to Singapore, a trade hub for ornamental fish in Southeast Asia. He is now a spritely 84-year-old with a full crop of white hair and many stories to share.

When Chew was 23, he started his pet fish business in 1963 in Penang. He commissioned Malay locals in Bukit Merah to collect fish from streams and lakes there. In 1967, one of his collectors brought him a dead adult fish* (see note at the end). Chew had never seen anything like it and was intrigued by the fish’s pair of barbels and big scales tinged with gold. “Get me small ones, alive,” Chew told his collector.

Chew sent a batch of the fish to his clients in Singapore, but nobody recognised it. Eventually, they found the name ‘arowana’ in a book. “But it had no Chinese name, so I looked at its barbels and scales and decided to call it ‘dragon fish’ (龙鱼),” says Chew.

His choice of name for the arowana made it popular. Demand from ornamental fish hobbyists grew, riding on the reverence in Southeast and East Asian cultures for the mythical dragon. Owners believed that arowanas brought them good fortune. Soon, Chew was sending more than a hundred arowanas to Singapore every month. Many others joined the hunt for wild arowanas in the Malaysian forests, says Chew.

Chew sold his first arowana juveniles at RM7 each in 1967. Four years later, the price had shot to RM500 (a lunch in Kuala Lumpur cost only 50 sen at the time).

A mere decade after Chew had sold his first Bukit Merah arowana to Singapore, Lake Bukit Merah and its rivers had lost most of their arowanas. Eventually, traders turned to Indonesia and found arowanas in Sumatra and Kalimantan. When asked if he had thought his collecting would endanger the fish, Chew says: “When everyone starts collecting, of course, it would become less and less.”

Haven no more

Johar bin Bakar recalled the time he began fishing at Bukit Merah in the early 1970s. Tanned and wiry, the 64-year-old is one of the few active fishermen in Kampung Selamat on the southern bank of Lake Bukit Merah.

There were few arowanas left in the lake then, says Johar. Still, “outsiders” would seek them. They would descend on the lake and streams at night, shining their torches into the water. When arowanas swim close to the surface, their eyes reflect red in the torchlight. If collectors failed on their first try, “they would return the next night with a net and encircle the arowanas,” he says. “They had to get them all.”

By the late 1970s, Asian arowanas contributed only 0.02% of total catch weight at Bukit Merah, according to a 1982 PhD dissertation by Yap Siaw-Yang. Yap, then a fisheries researcher at Universiti Malaya, checked fishermen’s catches between 1978 and 1981.

The situation was grave but not hopeless. An aquatic ecologist told Macaranga that if harvesting had been reined in, Asian arowana numbers could have rebounded. That is because Bukit Merah was still a relatively rich and safe environment for Asian arowanas in the 1970s and 1980s.

Yap recorded thriving fish numbers supported by healthy forests upstream. And when a teenage Johar went fishing for haruan but forgot to bring his drink, the lake water was so clean he could lean over the side of his sampan to quench his thirst.

CITES regulates international trade

Because many of the harvested Asian arowanas were sold overseas, regulators sought to restrict international trade. In 1975, the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) was established. It serves to protect species from the pressures of international demand. Species listed in Appendix I, which included the Asian arowana, were prohibited from commercial global trade, while those in Appendix II could be traded only with permits. Malaysia ratified CITES in 1978.

But CITES failed to stop the hunt for wild arowanas. In 1986, arowana trader Raymond Teng told The Star that he paid Orang Asli collectors for the fish – they were still bagging 50 big fish and up to 300 small ones from remote rivers. The price of the fish had rocketed. Teng said a “large and perfect specimen” could sell for RM10,000 – equivalent to RM25,000 today. Thieves broke into houses and pet stores to steal arowanas, while collectors trekked deeper into the forests. Traders saw the impending collapse of the wild arowana supply.

Today, it might seem puzzling that in the first two decades of arowana trade, nobody bred and farmed them. British fisheries officers in Singapore did try in 1927 but failed. By the 1970s, many other fish species were reared in tanks or ponds for food and the pet trade. Why not the arowana?

“We had no idea how they mated or laid eggs,” says arowana breeder Ng Hang Yong. They could not even tell male and female arowanas apart. The 63-year-old owner of Sianlon Aquatic Sdn Bhd in Batu Pahat, Johor, was one of the first to tackle the fish’s secret love life.

Ng eventually decoded the Asian arowana’s secret. His success allowed scores of breeders to have thousands of arowanas romancing in ponds. But that was not the future Ng had wanted.

Chapter 4: Into farms

In the mid-1980s, Ng was left with 30 adult arowanas when a big Taiwanese client suspended his orders. Each fish was longer than 30cm. He panicked. The fish fought in the crowded aquariums, losing scales and value by the day. Ng got tired caring for them. In frustration, he dumped them into a pond in his farm. “I couldn’t care less,” he recalls.

But a few years later, his Taiwanese client returned. When an exhilarated Ng ran a net through his pond, he found 21 surviving adult arowanas and – to his surprise – 11 juvenile arowanas! “I realised the adults must have given birth to these small ones,” says Ng. “Those were parents, I would definitely not sell them, no way!”

A lucrative future in sight, Ng began to buy adult arowanas in earnest. His parent stock grew to 700 adults. He spent the next few years studying his arowanas to maximise their reproduction.

Observing Asian arowanas is a nocturnal activity, as the fish swims near the surface only in the wee hours when the air is cool and damp. Ng pointed his flashlight at the ponds to pick out the red-reflecting arowana eyes. He climbed trees to watch them from above.

He found that sometimes, a pair of arowanas would huddle and move in tandem. They must be courting, he thought. Great, now what about the eggs?

Then he finally saw them. An arowana had breached the surface and opened its mouth. Ng saw the reflection of dozens of red eyes in the mouth. Could it be that arowanas carry their fry in their mouths? Ng confirmed his suspicious when he wrangled adult fish: one leaped at him and spat a mouthful of fry onto his face. It also gave him an idea.

“We could retrieve the fry from the mouth. We could be their nanny,” says Ng, as thrilled recounting this story in 2024 as back then. “Then the adults could start to brood again quickly and produce more young fish for me. I was so happy!”

Ng and his brother developed a routine of prying every fish’s mouth to collect fry a few weeks after they mated. They would then rear the fry with care and grow each to a 10cm fingerling in 2 months.

It was tiring but rewarding. “This fish brought me good luck and money, so I gladly give up my sleep to watch them with my flashlight.”

Ng kept his methods a secret. He even denied breeding arowanas when asked by Fisheries officers. But one day, a Japanese client visited his farm with a photographer. Unknown to Ng, photographs of his operations were later published in a magazine. “Anyone who’s smart could look at the photos and figure it out.” The secret went public in the 1990s.

At the same time, over in Singapore, another company called Rainbow Aquarium had been working for years with the Singaporean government to breed arowanas. In 1993, they succeeded with multiple generations of arowanas.

But while the future seemed bright for arowana farming, it was getting bleaker for wild ones. Almost two decades after CITES prohibited the commercial global trade of wild Asian arowanas, their populations continued to shrink. The ban alone was inadequate. CITES has, however, more than one way to dull the appeal of harvesting wild arowanas.

CITES allows for commercial trade of Appendix I species such as Asian arowana, but only if the individuals were bred and raised in captivity and met other specific conditions. This mechanism aims to flood the market with farm arowanas, crash the price, and cut the rewards of catching wild arowanas. Breeding facilities must acquire CITES permit and tag every exported captive-bred arowana with a microchip and unique serial number. It was a hopeful experiment.

Rainbow Aquarium reportedly became the first CITES registered facility for Asian arowana in 1994. By year-end, they had exported 300 arowanas to Japan for $1.47 million (about RM2.6 million at the time). Close on their heels, Ng’s Sianlon Aquatic also acquired CITES registration and exported to Japan from 1995.

A decade into the new millennium, arowana breeding and trading prospered. Even Hakim the angler sold arowanas at Bukit Merah when he was 18 and used the profits to pay for his wedding. Arowana demand reached record highs year after year, and farms sprouted. While the business would later stutter, Asian arowanas continued to proliferate in ponds like never before.

Meanwhile, wild arowanas faded from public attention. Virtually nobody championed their protection. But in ways that Ng had not foreseen, his breeding methods paved the way for the future conservation of wild arowana.

Continue to Part 2: A struggling Asian arowana trade provides opportunities for releasing farm arowanas into Lake Bukit Merah, but the fish now faces more threats in the wild than just overfishing.

Corrections/Updates. 12 March: Chew Leng Sye opened his pet store in 1963, not 1962. | 16 March: *Chew had told a different version of his first encounter with the Asian arowana to journalist Emily Voigt for her 2016 book. He had told Voigt that he saw a dead arowana at a roadside market and asked the fisherman to find him a live one. When asked about the different versions, Chew insisted to Macaranga that the version he told Macaranga is the correct one. Days after this story was published, Chew’s staff told Macaranga that Voigt’s version is correct. Since Macaranga cannot verify the accuracy of Chew’s recollections, we decide to mention both here.

This story was produced with the support of Internews’ Earth Journalism Network for Tracy Keeling.

Please email us to get copies of the materials.

- Indonesian President Presents Arowana to Japanese Emperor. 2023. Japan News.

- Battle of the Arowanas - World Championship in China. 2023. YouTube.

- Hui, T. et al. 2020. The non-native freshwater fishes of Singapore: an annotated compilation. Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 68, 150–195.

- Dream of Arowana (Episode 4). 2018. YouTube.

- AEB seeks partnerships to rear arowana. 2017. The Malaysian Reserve.

- Voigt, E. 2016. The Dragon Behind the Glass: A True Story of Power, Obsession, and the World’s Most Coveted Fish. Scribner.

- Ng, C. 2016. The ornamental freshwater fish trade in Malaysia. UTAR Agriculture Science Journal 2.

- Medipally, S. R., Yusoff, F. M., Sharifhuddin, N. & Shariff, M. 2016. Sustainable aquaculture of Asian arowana – a review. Journal of Environmental Biology.

- Shafiq, Z. Mohd. et al. 2014. An annotated checklist of fish fauna of Bukit Merah Reservoir and its catchment area, Perak, Malaysia. Check List 10, 822–828.

- Ikan hiasan – Ahmad Don. 2011. Usahawanjaya Blogspot.

- Rahman, S. 2010. Genetic variability and estimation of effective population sizes of the natural populations of green arowana, Scleropages formosus in Peninsular Malaysia. Advances in Environmental Biology.

- Rowley, J., Emmett, D. & Voen, S. 2008. Harvest, trade and conservation of the Asian arowana Seleroplages formosus in Cambodia. Aquatic Conservation Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 18, 1255–1262.

- Fish farm exports first batch to Japan. 1994. The Straits Times.

- Ismail, M. Z. Systematics, zoogeography, and conservation of the freshwater fishes of Peninsular Malaysia. 1989. PhD dissertation, Colorado State University.

- Yap, L. K. Putting a dragon in their tank. 1986. The Star.

- Yap, S. Y. The fish resources of Bukit Merah Reservoir. 1982. PhD dissertation, University of Malaya.

- Alfred, E. R. Conserving Malayan Freshwater Fishes. 1969. Malayan Nature Journal 22, 69-74.

- Alfred, E. R. 1966. An annotated bibliography of Malayan fresh-water fisheries. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 39, 145-165.

- Locke, A. The Fighting Kelesa. 1956. Journal of Malayan Angling Association 4, 461–463.

- Locke, A. Beyond the National Park. 1956. Journal of Malayan Angling Association 4, 422–428.

- Smedley, N. 1931. An Osteoglossid fish in the Malay Peninsula. Bulletin of the Raffles Museum Singapore, Straits Settlements.

- An Illustrated Guide to the Federated Malay States. 1923. Harrison, CW.

- Fisheries Department Report in Annual Departmental Report of Straits Settlements. (1927).

- Harrison, C. W. Illustrated Guide to the Federated Malay States. (1923).

- Maxwell, C. W. Malayan Fishes. Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 84, 177–280 (1921).

Tracy and Yao Hua first discussed this story in early September 2023. We did most of the reporting between December and early February. Writing started in late February.

We interviewed around 30 sources in Malaysia, Singapore, and the rest of the world. We spent 5 days in Bukit Merah (in a hotel with damp and peeling walls) and 2 days in Singapore; we spoke with breeders, fishers, arowana owners, and scientists at their farms, jetties, labs, and offices. Most of the interviews were done in person.

To reconstruct pre-1960s Bukit Merah, we referred to guides and government reports published before independence (1957). We spent 2 days at the National Library of Malaysia (the National Archive was closed for stocktaking). Many hours were spent reading digitised copies of old documents via the portals of libraries in Singapore and Cornell University. Researching all the arowana-related news stories in Malaysia from 1995 to 2023 at The Star’s office took us four hours.

But it’s not just our effort. Many others helped too, and only a few of them are named in the stories. We thank the researchers and arowana breeders who gave us their time and advanced our reporting. They helped us from the US, Europe, Singapore, Indonesia, and Malaysia.

Macaranga paid for field reporting, photos, reports, books, and company information. Our stories are free-to-read, and we rely on membership revenue to fund our work.

If you like our stories and appreciate our effort, please share our stories and support us -- be a member or contribute to our reporting funds. Thank you!

Related Stories

Popular Songbird Gets Trade Protection

No Fiercer Tiger Defender Than Kae

Support independent environmental journalism. Get exclusive insights. Sign up for our membership programme.

Pay us for our services to produce more stories like these. Note: This is not a donation; you are buying a service.

Comments are welcomed but shall be moderated. Do not use language that is foul, slanderous, violent or that may violate laws. Personal attacks will not be tolerated.