Floods might hog the current natural disaster news in Malaysia, but landslides are occurring too. Does Malaysia have what it takes to handle landslides?

CARRYING her one-month-old baby, Pricila Gracelyn rushed out from her hillside house in Penampang, Sabah in terror and pain as a big falling tree and cascading mud almost split her home into two.

“I was just about to lay my baby down on the bed when I suddenly heard a loud sound coming from above us. I thought it was thunder,” remembers Gracelyn.

“Maybe it’s my instincts, I carried my baby and escaped from the room, and in a blink [of an eye], our house was destroyed by the landslide.”

(Composite photo: Soil and trees destroyed Gracelyn’s house in Penampang, Sabah in September | Pics by Pricila Gracelyn)

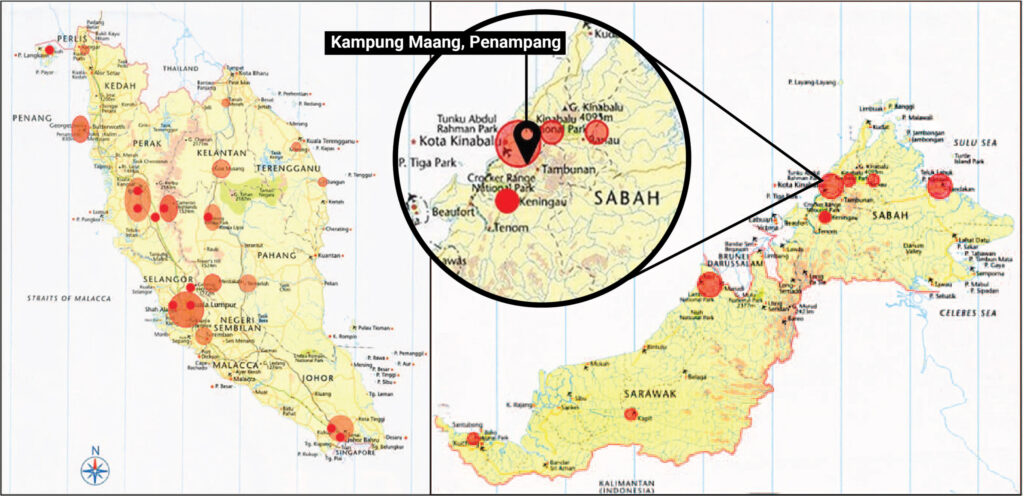

That was back in September. Gracelyn told Macaranga her village, Kampung Maang, had never experienced landslides before.

Likewise, unprecedented landslides are currently occurring in the peninsula. They are due to abnormally heavy rains caused by a tropical depression. At press time, the Public Works Department (JKR) recorded 40 landslides and 13 road collapses in 6 states, adding havoc to devastating floods.

Landslides increasing

Major landslides have made headlines in the second half of 2021, affecting thousands and claiming at least 11 lives. Following heavy rains, the landslides occurred on August 18 in Yan, Kedah; September 15 in Penampang, Sabah; and December 2 in Cameron Highland, Pahang.

A 2020 research paper on historical landslide events in Malaysia also revealed that since 1961, there has been an upward trend of landslide occurrences, with a death toll of more than 600 as of 2019.

The lack of intervention to prevent and prepare for natural disasters is mentioned repeatedly in academic papers and national master plans.

Yet, the current response to the ongoing disaster is proof once again that authorities are reactive rather than proactive. Furthermore, the authorities appear to be duplicating efforts and reinventing the wheel.

Who’s in charge

Several government departments and agencies manage landslide disasters. These include JKR through its Slope Engineering Branch and the Department of Minerals and Geoscience (JMG), while the National Disaster Management Agency (NADMA) was set up to coordinate overall disaster management efforts.

However, research shows that “each entity has its particular landslide disaster management practices”.

NADMA in particular is being heavily and widely criticised for its delayed and inadequate handling of the current flood and landslide disaster. Disaster management, it avers, is the joint responsibility of federal as well as state and district authorities.

After devastating monsoonal floods in 2014, the cabinet established NADMA in 2015 to lead national disaster management and preparedness effectively. NADMA’s website lists 10 functions and responsibilities (see below).

One of NADMA’s responsibilities is to prepare a national disaster risk management policy. Six years later in October 2021, it was announced that the policy was still “being formulated”.

Meanwhile, the Ministers overseeing NADMA seem to give a different picture of the agency’s roles. Last year in Parliament, the then-Minister said that the agency’s role was to manage floods; this year in Parliament, the current Minister said NADMA’s role was to handle compensation.

Both denied NADMA’S roles in preventing disasters.

NADMA was allocated a developmental budget of about RM129 million in the 11th Malaysia Plan (2016–2020). By the end of 2020 it had spent almost RM29 million.

The agency did not respond to Macaranga’s attempts to contact them since October.

Landslide master plan

Meanwhile, Malaysia actually has in place a master plan to handle landslides. It has been guiding hillslope management by JKR for over a decade. In 2004, JKR established its Slope Engineering Branch to mitigate, research, plan and investigate matters related to natural and man-made hillslopes.

The Branch developed the National Slope Master Plan to minimise the disastrous impacts of landslides.

Covering 15 years from 2009 to 2023, the master plan provides “a comprehensive and effective framework of national policies, strategies and action” to reduce nationwide landslide risks.

With 10 strategies, the master plan’s implementation should cushion people and economies from landslides.

Guidelines for slope design

The master plan has since been revised but JKR told Macaranga in a written reply that the revised plan is confidential.

However, the original master plan did state that technical documents and guidelines on slope designs be produced as part of loss reduction measures.

A key technical document is the Guidelines for Slope Design (2010), which continues to hold strong. JKR told Macaranga that “most of the slopes repaired by JKR [following the guidelines] have successfully prevented further failures and reoccurrences [of landslides]”.

The department is preparing new standard operating procedures detailing the workflow of every stage in slope management.

However, not every strategy in the master plan appears to have been fully realised. One example is an early warning system.

No warning in Penampang

Back at Kampung Maang, the landslide stranded Gracelyn and her family outside their wrecked hillside house for 2 hours. Neighbours finally helped them descend to seek shelter in the foothills. Then they had to wait till morning to leave the area because the main road out was flooded.

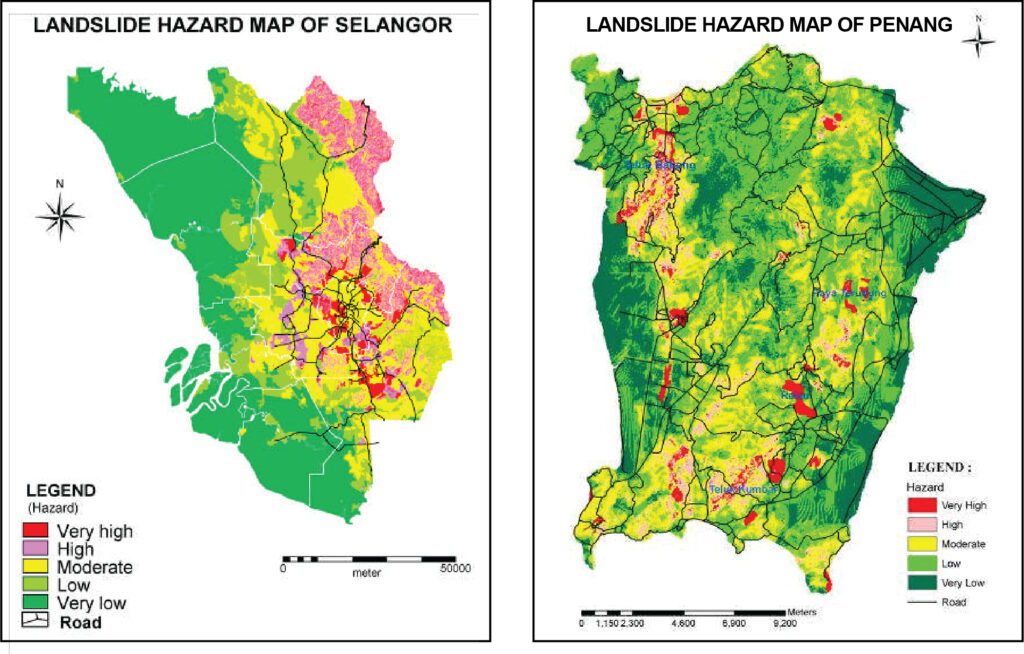

Kampung Maang sits in Penampang, already long identified as landslide-prone in JKR’s original National Slope Master Plan (see map). However, Gracelyn and her fellow villagers were unaware of this.

“There is no [awareness] campaign or programme about landslides and flooding before. In fact, I don’t even know what to do during landslides because I barely even have any knowledge about it,” says Gracelyn, adding that there was no alarm.

“We only shared information between us through WhatsApp.”

Early warning systems are part of JKR’s slope master plan. They can forecast landslides and alert surrounding residents, giving them enough time to respond to disasters. Beyond just technology to detect landslides, the deployment of early warning systems also provides an avenue for public awareness.

JKR explained that they had a budget to implement preventive measures such as developing hazard and risk maps, installing and maintaining early warning systems, and conducting public awareness and educational programmes.

In addition, JKR developed a new Integrated Slope Management System which will soon be used by the department’s officers at their headquarters as well as state and district levels.

“The allocation has been spent entirely,” said JKR.

Awareness growing

JKR pointed out that their slope safety awareness programmes also target not just the public but local authorities and other government departments.

Generally, awareness about designing, building and maintaining slopes is rising, said JKR. “The understanding of sustainable hillside development is growing amongst the industry players and there is improvement in complying [with] requirements on hillside development by developers.”

However, there are multiple requirements to which developers have to conform. “Each government agency and state authority have their own guidelines to be followed by developers and consultants,” said JKR.

“Therefore, we are trying to convey the information on hillside requirements to the developers so that they can come up with a comprehensive application and development plan.”

Federal road hazards known

For slopes that come under the purview of federal authorities, JKR said that hazard mapping for man-made road slopes along federal roads in Peninsular Malaysia was completed two months ago in October 2021.

But monitoring must also be done by local authorities too.

“As stated in the National Slope Master Plan, every hazard and risk map produced should be disseminated to all the state and district officers so that they could identify and focus on slope monitoring at hotspot areas especially during monsoon seasons.”

What’s up with our slopes

Nonetheless, why do so many slopes in Malaysia need maintenance?

In their slope management guidelines, JKR stated that between 2004–2007, “57% of landslides were due to human factor” and “most of the landslides occurred at man-made slopes”.

Cameron Highland is one well-known long-time victim of devastating landslides and has been undergoing intense hillside development. Research confirms that landslide hazards there are positively correlated with land-use change and increased physical development.

The highlands have not been spared from landslides in the current rainy season.

Controlling development

According to the National Slope Master Plan, controlling high-density construction and population density through effective land-use planning, could help mitigate disasters and reduce risks.

The master plan also encourages state and local authorities to utilise hazard maps in their land-use decisions.

One independent 2017 study concluded that entirely avoiding landslide-prone areas for development is the best solution to prevent landslides.

Reinventing the wheel

Besides questionable land-use change decisions, authorities also appear to be duplicating systems and plans already supposedly in place.

A month before the landslide that hit Gracelyn’s Penampang kampung, major landslides occurred in Yan, Kedah. The water surge phenomenon, or as the locals called it – kepala air – claimed 6 victims.

In response, the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources announced plans for a multi-agency expert task team looking at geological disasters. They also announced that the Minerals and Geoscience Department (JMG) would install early warning systems, conduct risk mapping and run public awareness programmes.

These appear to be a replication of efforts already being made by JKR. This lack of coordination between different agencies has been identified in 2017 as a major issue in disaster risk management by researchers mapping disaster management in Malaysia.

There are 79 agencies at federal, and state and district levels responsible for activities related to disaster risk management in Malaysia, say Dr Noraini Omar Chong and Dr Khairul Hisyam Kamarudin in their 2017 research paper, ‘Issues and Challenges in Disaster Risk Management in Malaysia: From the Perspective of Agencies’.

They have mapped out the roles and responsibilities of these agencies according to pre-disaster and post-disaster categories, and highlighted the 3 major issues in disaster management:

(1) too much emphasis on top-down approaches, therefore overlooking community involvement,

(2) lack of coordination in the entire disaster management cycle, with too much focus on disaster emergency response, and

(3) lack of planning of a long-term recovery (post-disaster) process.

Noraini is currently with PLANMalaysia and Khairul is with Universiti Teknologi Malaysia.

For example, JMG recently published on Twitter (reproduced below) critical slope location maps for each state, following their 2021 monitoring exercise. The department identified 122 highly critical slopes that could potentially be geological landslides risks. Most are located along federal roads.

These critical slope location maps could actually feed into hazard and risk maps and benefit land use planning.

In the face of the climate crisis, extreme weather events are becoming more frequent, including heavier rain that can trigger massive landslides in hillsides made vulnerable by human activity.

The call is for proactive preparation rather than a “late alert” for unusual weather conditions and their consequences. Involving local communities in the disaster risk management process and tapping into local knowledge are key.

Penampang landslide victim Gracelyn says it was better to equip villagers like herself who live in remote hilly areas.

“Since we never know when disasters are going to happen, the NGOs or the government can at least supply things such as rescue boats to every kampung so that the villagers won’t have to depend on the rescuers.”

About 3 months after the landslide, Gracelyn is currently staying in the nearest town while rebuilding her village house. “I still have panic attacks every time the rain comes,” she says.

[Edited by SL Wong]

Chow Mei Mei (@mmeichow) is a Macaranga Sprouts journalist.

We thank the supporters of the Sprouts initiative who made this story possible.

Abd Majid, N., Taha, M. R., Selamat, S.N. (2020). Historical landslide events in Malaysia 1993-2019. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 13(33), 3387-3399.

Abdul Rahman, Haliza & Mapjabil, Jabil. (2017). Landslides Disaster in Malaysia: an Overview. Health and the Environment Journal, 8, 58-71.

IPCC. (2012). Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation. A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (582 p.). Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kadir, M.F.A., Razak, K.A., Ahmad, F., Khailani, D.K. (2021). Risk-Informed Land Use Planning for Landslide Disaster Risk Reduction: A Case Study of Cameron Highlands, Pahang, Malaysia. Understanding and Reducing Landslide Disaster Risk. WLF 2020. ICL Contribution to Landslide Disaster Risk Reduction.

Mohd, S., Fathi, M. S., Harun, A. N., & Omar Chong, N. (2018). Key Issues in the Management of the Humanitarian Aid Distribution Process During and Post-Disaster in Malaysia. PLANNING MALAYSIA, 16(5).

Omar Chong, N., & Kamarudin, K. H. (2018). Disaster Risk Management in Malaysia: Issues and Challenges from the Persepctive of Agencies. PLANNING MALAYSIA, 16(5).

Roccati, A., Paliaga, G., Luino, F., Faccini, F., & Turconi, L. (2021). GIS-Based Landslide Susceptibility Mapping for Land Use Planning and Risk Assessment. Land, 10(2), 162.

Satyam, N. (2021). Landslide prediction and field monitoring for Darjeeling Himalayas: A case study from Kalimpong. Basics of Computational Geophysics, 165-188.